Plastic Flowers

The scrub-clad courier of death, with the paper mask bunched up under his chin, and the sharp hospital breath. My imagination had been off by one shade of brown in his eyes, raw umber, and the sandpaper stubble on his face. His voice was like sandstone, it came with the shrill ringing grind like a door to a hidden passageway in an Indiana Jones movie; and the chilling detatchment in his stare could not be far from the musty stillness and emptiness of a tomb full of bleached bones. The divots on the sides of his nose were still purple from the weight of the glasses. He never knew her and yet he got to watch her die while I sat out in the corridor with the silly blue paper booties that looked like shower caps, pulled over my shoes. With the cheap sconces and dusty plastic flowers. Buttercups the color of banana Laffy Taffy. Here. The years had deposited me in here in this moment with fake flowers to mock my turmoil. "We lost the baby..." His words echoed off of the corridor walls. The plastic flowers listened eagerly. We lost the baby. And who's "We?" Because he's telling me that they couldn't stop the hemorrhaging. Iestyn. We'd fought over what his name would be. And now he was like a forgotten dry-cleaning order. I'd never even know where they buried him and I'd never care because he killed her. She's gone. He's telling me she's gone, serving it up cold on the roughly hewn slab of sandstone. Did I want to see her before they took her down to the morgue. Did I want to see her.

She always got surly and irritable when she was hungry. She let it slip later that it had something to do with bloodsugar. Theretofore, I'd taken it personally. She'd come home in a fowl mood and I'd just go into the kitchen with her words following me, gnawing on my heels like rabid min pins (miniature doberman pinschers, the dumbest and meanest dogs ever bred.) I'd just cook something for her and she knew what I was doing and she hated it. Always the shame and downcast eyes and softness in her voice after she had eaten. I never minded. There's always a reason for people's bitchery, even when there's not an excuse. Always a reason for it. And if you know them well enough, you'll know their reasons and you'll just smile sadly and knowingly inside of yourself when they send their min pins to gnaw on your ankles.

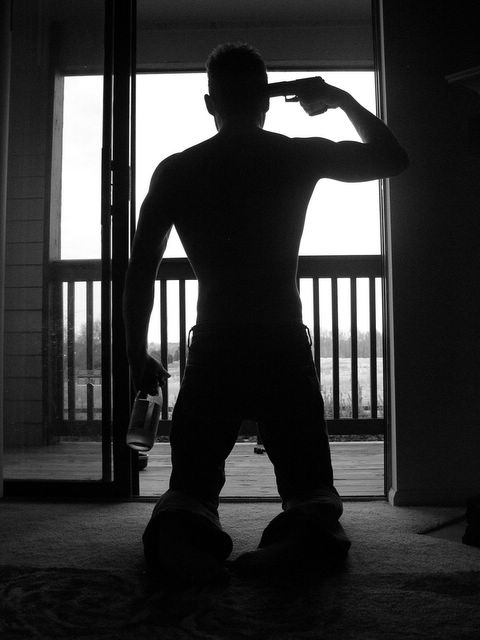

We used to go down to the basement of Ramsey hall, down where Suhling's labs were. Dr. Tippur, Medhat, and I. We had a huge optics bench down there that was the size of a large billiards table. It was covered with what looked like a hap-hazzard game of chess with the beam-splitters and lenses and mirrors that stood waiting for the green laser. All configured to produce a Coherent Grating Sensing Interferometer, per Dr. Tippur's scrupulous calculations. And we had a pneumatic ram for shattering the fracture test specimens. The ram's tup had a strip of copper tape fixed to the leading edge. And copper tape on the top edge of the test specimen, too. When the ram came crashing down, the copper tape on the tup would touch that on the specimen and the circuit would close, sending a signal to the shutter to expose the film. The film in Dr. Tippur's fantatstic high speed camera. A dinosaur of a camera that looked like a relic from a battleship with the gray bumpy flecked paint like you see on vintage slide projectors, the kind that smell like an electrical fire and burning cardboard. It was so big that it had wheels. 2000 plus frames per second. And all we had in it was a thirty-frame roll of 35mm film. That'd buy us 15 milliseconds of footage. And that was still sloppy because we were filming a crack that was propagating at nine-hundred and eighty million meters per second squared. That's ten to the eighth times the acceleration of gravity. I know! I was shocked also. The lights would go out and sometimes on cold days, you could see the lazer if Hashem and Yassir had been smoking inside. I'd stand in the corner next to the CO2 tank and twist the valve open when Tippur gave the signal. The instrument panels glowed like Las Vegas. I always wondered why we never had an oscilloscope in there. One of the old ones with the green and black display monitors. Because it never feels like science without an oscilloscope in the room. The air hose would writhe and hiss and the turbine in the camera would whine as it spun the mirror up. And I would get chills because I thought that fracture mechanics was what I was passionate about. But later, grad school would just be another bad descision and so would marriage, so would all the times I never went on the 0.40 caliber, 145-grain, jacketed hollow-point diet.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home